In Pakistan, Democracy Exists by the Army’s Permission – Analysing the Politicized Lecture for India from World’s Most Politicized Army

When a Pakistani four star-general Sahir Shamshad Mirza — among the top military men in Pakistan — gets on the world stage wagging a finger at India, the world should pause and look at the mirror behind him. This carefully-orchestrated chorus of “India’s military is politicised, and India’s polity is militarized” sounds strikingly ironic coming from Islamabad, where the generals don’t just lecture democracies — they actually run the state.

Pakistan insists on pointing at India’s shortcomings while conveniently ignoring the fact that in their own country, the uniform and the ballot box are inseparable–and the military writes more constitutions than any legislature ever dared.

For a Pakistani politician or military man, claiming moral high ground or levelling allegations about India’s “politicised military” is as hollow as a drum echo from Rawalpindi.

Mirza’s lament that “the next war won’t stay limited to Kashmir” is an admission in disguise. Let’s read it properly: Pakistan is openly signalling that its strategy isn’t bound by the dust of the Line of Control anymore. It is willing to admit to cross-border terror, to regional destabilisation, to its intention of widening conflict.

What Pakistan casts as a lament about Indian aggression, in fact reads like a blueprint for its own aggression. It’s the military’s drumbeat of expansion, dressed up as victimhood. While Pakistan’s generals pretend to lament escalation, they in effect own responsibility for lowering every threshold of violence they later decry.

Pakistan lectures India on “dominance” when it cannot dominate its domestic politics without the army’s control

Let us examine Mirza’s boast: “We fought 96 hours on our own resources.” He says this as if it absolves Pakistan of its myriad dependencies — Chinese drones, Iranian fuel deals, endless IMF bailouts, foreign military relationships hidden in plain sight. When you attempt to rebrand borrowed weapons, imported fuel and international bailouts as “own resources,” you mock the notion of self-reliance. Meanwhile, India quietly builds its strength through its economy, technology, and civilian democratic institutions — which Pakistan keeps lecturing India over. Pakistan claiming resource-independence while lying under a mountain of debt and external patronage is less of a boast and more of a confession of desperation.

Pakistan’s generals lecture democracies while they quietly groom their own ghost governments. They bandy phrases like “civilian supremacy,” yet the civilian never moves a muscle without the general’s nod

The Pakistani leadership says India uses “military power and Western support for dominance.” For a country that has survived by begging for IMF lifelines, relying on foreign lenders, treating its own polity as a puppet stage for the military’s ambition, Pakistan’s hypocrisy stinks. India uses its own industrial base, its own demographic dividend, its own democratic credibility to assert itself. Pakistan uses external hand-outs, military co-op programmes, and the threat of instability as bargaining chips. The irony is stark when Pakistan lectures India on “dominance” when it cannot even dominate its own domestic politics without the army’s thumb in the kitchen.

When Pakistan asks for observance of United Nations Security Council resolutions on Kashmir, they conveniently forget that the same resolution demands a beginning of withdrawal of Pakistani troops from what it calls Azad Kashmir and Gilgit-Baltistan. Pakistan never withdrew; it fortified. On that metric alone, Pakistan fails the test it sets for its neighbour. Mountainous prose about UN-mandates turns into flat jokes when your own forces occupy someone else’s territory in defiance of the world body you invoke.

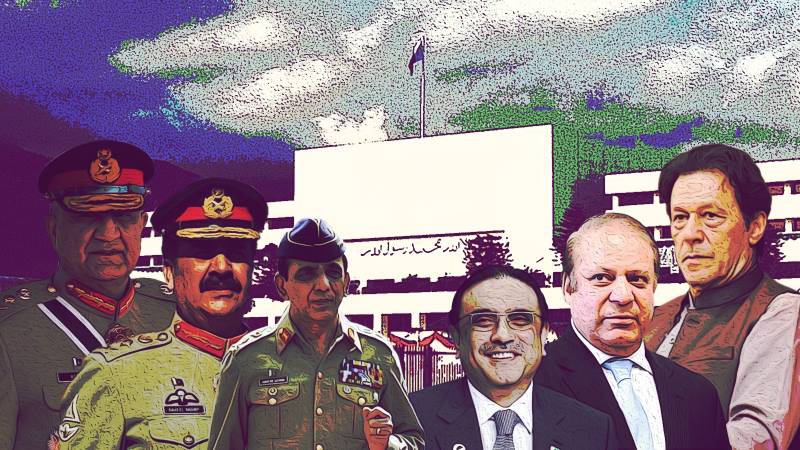

A State Run from the Barracks

The military in Pakistan picks prime ministers like class monitors, drafts and re-drafts constitutions like teenage rebels writing graffiti on walls, intervenes in every election and every government-transition. Over the last 70 years, Pakistan’s political-military history reads like a chronicle of interventions and instability.

Since it was formed in 1947, Pakistan has had 17 Army Chiefs and 24 Prime Ministers—excluding caretaker Prime Ministers. The majority of the PMs have not completed a full five-year term. Pakistan has endured three direct military coups (1958, 1977, and 1999) and multiple indirect interventions, during which elected governments were dismissed under pressure from the military establishment. Of its prime ministers, one was hanged (Zulfikar Ali Bhutto), two were assassinated (Liaquat Ali Khan and Benazir Bhutto), several were exiled (including Nawaz Sharif and Benazir Bhutto), and many were jailed or disqualified through judicial or military manoeuvring. The military, meanwhile, has enjoyed unbroken institutional continuity.

The imbalance is structural: while politicians are expendable, generals are untouchable. These figures reveal that in Pakistan, democracy exists by permission, not by permanence.

In Pakistan, it is a military that governs by shadow, that governs by force, that governs by fear. And yet, it feels righteous enough to accuse India’s armed forces of being politicised. There is no other term for that than hypocrisy. Pakistan’s generals lecture democracies while they quietly groom their own ghost governments. They speak of democracy without ever relinquishing their own control. They bandy phrases like “civilian supremacy,” yet the civilian never moves a muscle without the general’s nod.

In Islamabad, major decisions don’t come from the parliament. They come from the barracks. From the commanding officers. From the whisper network of intelligence and uniform. That reality doesn’t neatly enter the diplomatic pronouncements, but it looms large behind them. When you accuse your neighbour of turning polity into military and military into polity, you should first turn the mirror on yourself.

Pakistan’s military-industrial-political complex isn’t the exception – it is the rule of the state. Meanwhile, the drum of Pakistan’s military beats loud: “India is aggressive. India wants regional hegemony. India uses military might and Western friends.” Fine — take a look at Pakistan’s maps. Where is the restraint? Where is the documented non-interference? Where is the unbroken commitment to peace?

If the Pakistani state were serious about peace, it would disarm its proxies, withdraw its forces from occupied regions, shift resources away from military antagonism into schooling and hospitals. But instead, it doubles down on anti-India rhetoric, leverages terrorist groups, uses Kashmir as a bargaining chip, and still expects the world to stand in solemn awe of its moral stance.

Seventy Years of Command and Chaos

The truth is that Pakistan’s military has institutionalised aggression. It has institutionalised terror as policy. It has institutionalised the blurring of lines between wartime and peacetime, between soldier and civilian, between state and non-state. And yet it stands in the world telling India to respect restraint. That is not only hypocritical — it is dangerous. Because when you are operating from a lie, you weaken your strategic credibility. When a country lectures on peace while arming conflict, it becomes part of the problem – not part of the solution.

Look at the Pakistani claim: “We fought 96 hours on our own resources.” That was during the latest four-day escalation with India. But the fight did not stay within Kashmir. The cities were targeted; the border was transgressed. That “own resources” speech is a self-parody, because Pakistan continues to rely on debt and external crutches to keep its military machine alive.

The Pakistani polity may be civilian on paper, but the army’s hand remains omnipresent — running policy, running economy, running foreign affairs. How can the army then turn around and ascribe politics and militarisation to its neighbour? Either you believe war should be civilian-controlled — in which case Pakistan must hand over governance to civilians. Or you accept that your system is militarised and stop pretending your neighbour’s is worse.

At the same time, India doesn’t play the victim card for every bump on the border. India doesn’t make every skirmish into a moral crusade. India doesn’t beat the drum of victimhood while arming terror-governed proxies. Pakistan does. And it wants the world to nod along. That won’t happen. You cannot lecture others on democracy while you live under recourse to martial law. You cannot lecture others on civilian supremacy while your generals choose your prime ministers. You cannot lecture others on non-militarisation while your state trains terrorist proxies as alternative forces.

Pakistan keeping its military in supreme command of everything makes the country lose credibility on its claims of democracy. Pakistan’s generals wield far more power than any Pakistani prime minister, far more than any Pakistani parliament.

And yet they claim that India’s polity is militarised, and India’s military is politicised. The joke is on the world, and the joke is on them. What Pakistan needs to do — if it is serious — is to shrink the military’s hold on society, let real democratic politics thrive, end its patronage of terror and cross-border mischief, align its words with its deeds.

Until then, every sermon its army gives about India’s militarisation will just be echoing from the halls of its own dictatorship. Until then, the world should hear the drumbeat not as a call for peace but as a drum signalling Pakistan’s persistent hypocrisy: violent, unstable, state-sanctioned, and lecturing others about morals. Until then, whenever General Mirza and his colleagues in Pakistan’s military leadership pontificate about Indian militarisation, we don’t just hear the words — we hear the noise of a system mocking itself.

(Got a fresh perspective? C-KAR invites original articles and opinion pieces that haven’t been published elsewhere. Send your submissions to deputydirector@c-kar.com)

Dr Syed Eesar Mehdi is a Research Fellow at International Centre for Peace Studies, New Delhi, India