In Balochistan, the Shadows of the Disappeared: Grief as Politics Of Testimony

The Baloch conflict has never simply been about autonomy, insurgency, or territorial discontent. It is about betrayal repeatedly stitched into the historical fabric of the Pakistani state’s relationship with its most resource-rich and yet politically alienated province. From the forced annexation of Kalat in 1948 to the armed insurgencies that followed—each one more fractured, more subterranean, more desolate—the state has responded not with reconciliation but with repression, not with inclusion but with invisibilization. Enforced disappearances have become the unspoken grammar of governance in Balochistan. Young men—activists, students, poets, teachers—vanish without record, often never to return.

In this scorched landscape, where law fails and speech is punished, it is the women—the mothers, the sisters, the wives of the disappeared—who have emerged as the unyielding conscience of a region.

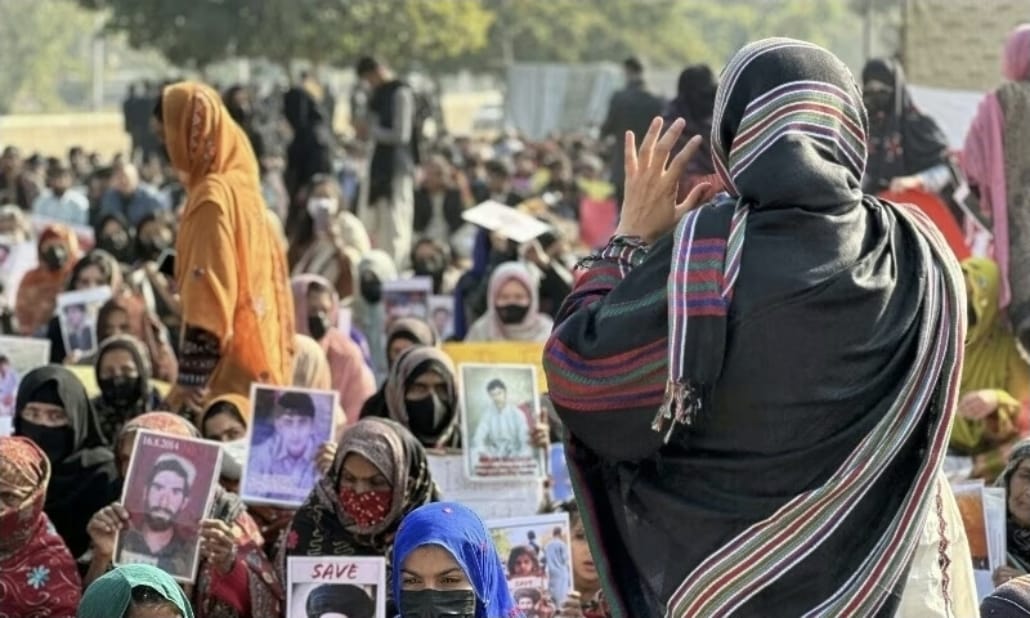

In every political system that survives on erasure, it is memory—not ideology—that becomes the most destabilizing force. Nowhere is this more evident than in Balochistan, where the landscape has been etched not merely by conflict, but by systematic disappearances. In the last two decades, a new form of political presence has emerged in this geography—one that does not wear the insignia of the party, does not wield arms, and does not even speak in the idioms of constitutional rights. It sits silently, at times for years, on pavements and protest camps. It holds up laminated photographs. It asks a single question: Where is my son?

The women of Balochistan—especially the mothers and sisters of the disappeared—are living a form of resistance that defies conventional categories. Their grief is not merely personal. It is the residue of state violence that cannot be metabolized through compensation, reconciliation, or procedural justice. It is also not incidental.

It is structural—produced by the logic of counterinsurgency, by the architecture of security exceptionalism, and by a national consciousness that has learned to live with the idea that some regions are dispensable and some lives uncountable. In such a context, to mourn publicly is to stake a claim not just on loss, but on truth.

The Enforced Disappearances of Balochistan

The state’s war in Balochistan has always been more ontological than territorial. What it fears is not merely rebellion, but the articulation of Baloch subjectivity outside the frame of state benevolence. And so it does not always kill—it makes individuals disappear. It deletes bodies without acknowledgment, creates bureaucratic invisibility around lives, and fractures families through ambiguity.

Enforced disappearance is not merely a human rights violation—it is a political technique. It is disorienting. It paralyzes. It renders the family incapable of moving on, and the state incapable of being held accountable.

This is where mourning becomes politics. Not because it is loud or disruptive. But because it is unmanageable. The mothers, who sit in front of the Quetta Press Club or walk barefoot for hundreds of kilometers to Islamabad, do not ask for policy. They ask for acknowledgement. And in doing so, they upend the moral economy of the State. The disappeared son is no longer merely an individual. He becomes a symbol of the ungrieved citizen, whose erasure was necessary for the state to imagine order.

One might ask, what comes of all this? Does this mourning yield change? Does it alter policy? Perhaps not. But it does something more fundamental. It renders the state’s silence illegitimate

American philosopher Judith Butler’s (2004) work on precarious life is useful but insufficient. It tells us that not all lives are equally grievable—that the state’s own imagination determines which deaths matter. But the Baloch mother does more than mourn. She forces the life of her son back into the public. She doesn’t just grieve him; she performs his personhood again and again. Each repetition is an interruption in the nationalist narrative. She refuses closure. And in that refusal, she reclaims history.

What makes this form of politics unsettling to the state is that it cannot be appropriated. These women are not seeking electoral recognition. They are not bargaining with bureaucrats. Their politics is not about outcomes, but presence. As noted anthropologist Veena Das (2007) reminds us, violence becomes most durable when it folds into the everyday. In Balochistan, the everyday is political precisely because the violence is never declared—it is only suffered. Mourning, in this context, is not a reaction; it is a form of living. It is the only way to resist the unnameable.

The Deafening Silence around Baloch Mothers

And yet, the silence around these women is deafening. National television rarely shows them. Political parties rarely mention them. Courts rarely prioritize them. The silence is not accidental. It is pedagogical. It teaches the rest of the people what to ignore.

The Baloch woman mourning her son becomes the state’s blind spot—visible, but unacknowledged. Present, but uncounted. The cost of this silence is not only local. It is national. Every democracy that forgets its victims teaches itself how to lie.

The woman who mourns thus becomes the last institution left in Balochistan that holds the state morally accountable. She is not interested in revenge. She is not seduced by political ideology. Her politics is made up of a kind of exhausted determination. It is not designed to win, but to haunt. And that haunting is not metaphorical. It is literal. Every day she sits is a reminder that the state has something to hide.

Gendered Grammar of Political Resistance in Pakistan

These women disrupt the gendered grammar of political resistance. Baloch politics has long been narrated through the masculine language of insurgency. The militant, the rebel, the fighter. But these women enter politics through a different door. Their entry is neither exceptional nor performative. It is domestic, ordinary, slow. And precisely for that reason, it is devastating. They are not revolutionaries. They are caretakers of memory. But memory, in a state organized around forgetting, is more dangerous than a gun.

Their resistance is not strategic. It is ethical. That distinction matters. Strategy operates within the logic of negotiation. Ethics refuses it. The Baloch mother who mourns is not looking for a resolution. She is not even looking for comfort. She is performing an unflinching fidelity to truth. In a state where the truth has no institution, that fidelity becomes the last source of legitimacy.

There is a further dimension that must be confronted: the state’s deep allergy to women occupying public space in this manner.

In Baloch society, as in many others, women are often expected to remain within the domestic sphere. When they step into public space, they are seen as violating not just a norm, but a boundary. The state weaponizes this: it ignores them, dismisses them, sometimes surveils them. But what it cannot do is accuse them. The mother mourning her disappeared son is the one figure even the state cannot publicly criminalize. And therein lies her untouchable power. She becomes the one citizen who cannot be delegitimized without revealing the full violence of the state.

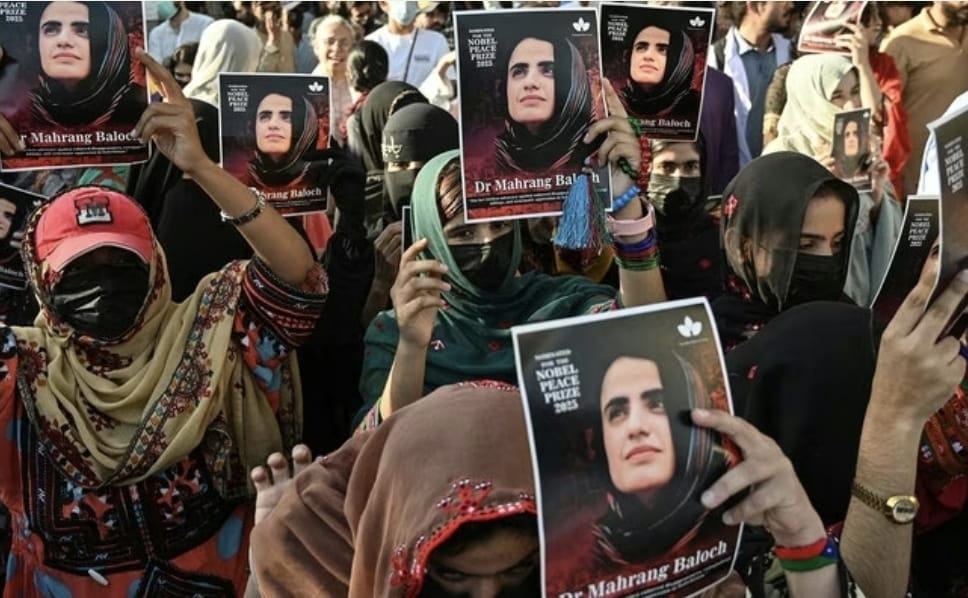

This brings us to a disturbing, but necessary point: The Baloch women who mourn have done more to expose the limits of Pakistani claims to democratic legitimacy than many reports, many speeches, many judicial inquiries. Their insistence on presence, on memory, on the body, destabilizes the state’s neat fictions of control. They are not separatists. They are not militants. But they have mounted one of the most profound ethical critiques of state power in South Asia today.

One might ask, what comes of all this? Does this mourning yield change? Does it alter policy? Perhaps not. But it does something more fundamental. It renders the state’s silence illegitimate. It prevents the normalization of violence. And most crucially, it refuses to allow the rest of the nation the comfort of forgetting. That is no small thing.

The mothers of Balochistan are not asking for revolution. They are asking for memories. And in that, they continue to expose the deepest wound of the state: its refusal to remember those it has wronged.

(Got a fresh perspective? C-KAR invites original articles and opinion pieces that haven’t been published elsewhere. Send your submissions to deputydirector@c-kar.com)

Dr. Irfan Ul Haq and Dr. Zahid Sultan hold PhDs in Political Science and are working as independent researchers